Art: An Unconscious Revelation of Trauma & Recognising our own Emotional Wounds

- Dr. Maria Z Kempinska

- Dec 18, 2025

- 4 min read

Written by: Dr. Maria Z Kempinska, MBE, PhD, MA, BACP

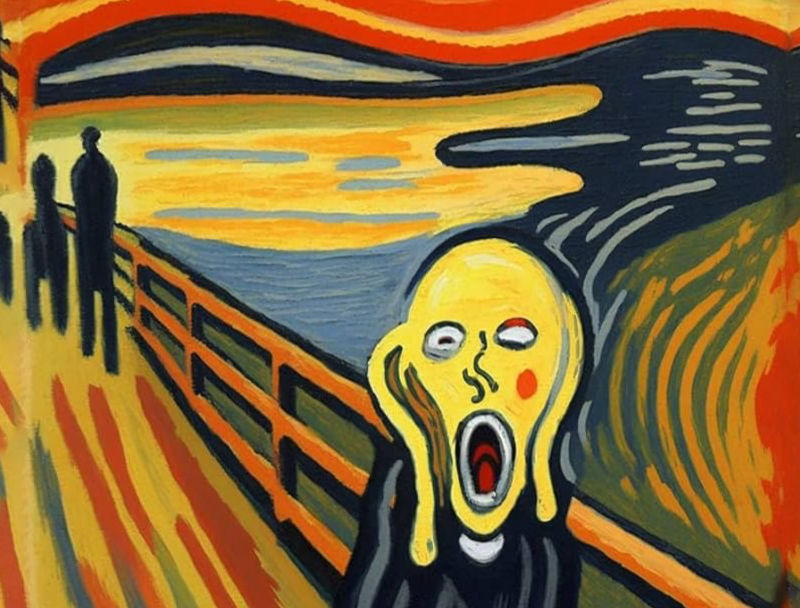

The silent scream resonated with the world.

Your art or writing can reveal trauma that has shaped your life, often

without you being fully conscious of it. By paying attention to unconscious

creative expression through art, doodling, prose, or poetry, you may begin to

uncover what lies beneath the surface. These forms of expression can

become powerful channels for revealing inner feelings, anxieties, and fears

that words alone may not access.

Trauma frequently generates deep anxiety, particularly when it involves loss.

For many reasons, this anxiety can show up as fearful or hypervigilant

behaviour. Whatever the nature of the loss, it is important to understand

that, in most cases, it is not your fault. Trauma is not a life sentence; it can

be understood, managed, and ultimately reconciled.

I use the following painting as an extreme example of loss and creative

expression emerging from profound inner turmoil—an experience that

formed the emotional foundation of Edvard Munch’s life. The traumatic

events themselves deeply affected Munch, but so too did the emotional

environment in which he lived long after the losses occurred.

Edvard Munch was 29 years old when he painted The Scream in 1893. The

renowned Norwegian artist, best known for this iconic work, experiencedsignificant trauma in childhood that profoundly shaped his art. He later wrote

a poem connected to the painting:

“The sky turned blood red…

I stood trembling with anxiety,

and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

Born in 1863, Munch grew up in a household marked by illness, death, and

emotional turbulence. When he was just five years old, his mother died of

tuberculosis, leaving him and his four siblings in the care of their father—a

strict and deeply religious man whose beliefs were often infused with fear

and negativity. His aunt later came to live with the family. The early loss of

his mother created a lasting sense of vulnerability, sorrow, and depression

that followed Munch throughout his life.

John Bowlby, in Separation and Loss, explains that early traumatic loss or

disruption in the bond with a primary caregiver can create deep

psychological wounds. Such disruptions impair a child’s sense of safety and

may lead to anxiety, disorganised attachment, and long-term emotional

difficulties, including depression, grief, and relational struggles in adulthood.

Munch’s life provides a striking illustration of this theory.

His trauma was not the result of deliberate harm; rather, life unfolded

tragically around him. The loss of his mother was compounded when his

older sister Sophie, his closest companion, also died of tuberculosis at just

15. Her death profoundly affected him. The pattern of loss continued: his

younger sister later developed mental illness, and Munch himself struggled

with chronic illness, depression, anxiety, and an enduring fear of losing his

sanity. He suffered from tuberculosis and lived with persistent concerns

about his mental health.

His father’s rigid, apocalyptic religious fervour added another layer of

emotional strain. Illness was interpreted as punishment for sin, leaving

Munch burdened by guilt and fear of divine retribution. Much of this

emotional torment found expression in his art, particularly after his father’s

death in 1899.

These early experiences of grief, illness, and instability permeated Munch’s

work, which frequently explored themes of anxiety, death, and human

suffering. He once described illness, insanity, and death as the “black

angels” of his life. Art became his means of processing and giving form to

emotional pain rooted in childhood trauma. His unfulfilled love affair with Millie Thaulow, the wife of a distant cousin, plunged him into further despair. His father would have strongly

disapproved, yet Munch was mesmerised by her.

What motivated this relationship? Was it an unconscious attempt to assert independence from his father’s authority or even to punish him retrospectively? Was he drawn

to the unattainable, repeating earlier experiences of loss when Millie ended

the relationship after two years?

Once again, art became his refuge,

bringing anxiety, guilt, and fear to the surface:

“I was stretched to the limit. Nature was screaming in my blood…

after that I gave up hope of ever being able to love again.”

Trauma can be understood, repaired, integrated, and healed with the right

support. Emotional wounds take many forms and occur across all cultures,

backgrounds, and stages of life. Perhaps part of our life’s purpose is to

understand how we were wounded and how that wound might ultimately

be transformed into a source of insight and healing.

So how do we recognise our own emotional wounds?

Difficulties in relationships, where fear of loss leads to pushing others

away

Striving for perfection in relationships, which is ultimately unattainable

A lack of emotional security that destabilises present connections

Repetitive patterns, behaviours, or choices that feel out of alignment

with your values

Fear of financial ruin despite being objectively safe

Ongoing fear of losing relationships without clear cause

Suppressed feelings hidden to please others and avoid conflict

Guilt rooted in misunderstood childhood experiences and carried

unnecessarily into adulthood. Recognising these patterns is often the first and most important step toward healing.

✨ If you’d like to explore trauma work with Dr. Maria, get in touch with us today.